Tuesday 30 June 2009

Who fired?

"A number of shots have been fired at a house in the Rossdale area of Ballymena, County Antrim. It happened at about 0030 BST on Tuesday. A man and woman in the house at the time were not injured. DUP councillor John Carson, who condemned the attack, said there had been tensions in the area over flags. He said it was the second attack on the property, which belongs to a member of a local community association. Councillor Carson said there had been a "deal done on flags last year" that they would be put up on 1 July and taken down on 31 August. However, he said this year someone had "taken it upon themselves" to put flags on every lamppost in the development. He added that the woman whose home was attacked approached those putting up the flags."

That is already bad – very bad. But it raises a particularly interesting question: whose gun fired the shots?

The Ulster Volunteer Force and Red Hand Commando confirmed that they had completed the process of rendering their arms and ammunition totally, and irreversibly, beyond use on Sunday. The UDA, although only 'starting to decommission' stated that "there is no place for guns and violence in the new society we are building."

So who fired the shots? Are there other loyalist groups that have slipped under the radar, or is one of the loyalist groups (as so often) lying. The identities of the flag-erecters, and their friends, are presumably well-known both locally and to the police, so it shouldn't be too hard to find out.

Yet again the close relationship between the unionist/loyalist flag fetishists and loyalist terrorists is displayed. And they wonder why normal people are repelled by their flags?

The Death of Sheila Cloney

"A member of the Church of Ireland, her decision 52 years ago to flee her Catholic husband and the State rather than allow her children to be educated at the local Catholic national school led to a boycott of Protestant businesses in the south Co Wexford village."

The incident was a notorious cause celebre at the time and particularly attracted the attention of northern unionists, including the young Ian Paisley. It is still referred to from time to time by some unionists, particularly those who try to portray the south as a priest-ridden land.

Unfortunately for the unionists, their superficial reading of the situation appears to be incorrect. Certainly the disliked Ne Temere rule had a part to play, but when the local Catholic priest tried to insist on the Cloneys adhering to their commitment to raising their children as Catholics, Sheila refused, partly at least because of the arrogant and bullying manner in which the priest acted, and fled the area and the country.

After a while the Cloneys got back together and Sheila and the children returned to County Wexford where, as a compromise, they were educated at home.

The priest organised a boycott of Protestant businesses in Fethard-on-Sea as a sort of collective punishment. This boycott was condemned in Dáil Eireann by the Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera, and by Seán Cloney, who said later that "I totally rejected the boycott. It caused a lot of trouble for me. My main support in breaking the boycott came from Old IRA men who themselves had fallen out with the clergy during the War of Independence."

So it seems that the situation was much more nuanced than some northern unionists think – the positions of the IRA and the leader of republican Ireland were similar to those of northern unionism, and ultimately neither Sheila nor Seán Cloney obeyed the orders of the Catholic priest, and both returned to live out their lives in Fethard-on-Sea. It seems that the south was not so priest-ridden, either at the individual or the state level, as it is sometimes claimed to have been.

Monday 29 June 2009

The TUV tries to broaden

The problem is, of course, that while a one-man-band may be all you need for the European Parliament election where no party is ever going to get more than one candidate elected, it is clearly an inadequate strategy for the upcoming Westminster election, and especially inadequate for the Assembly elections in 2011.

So the TUV has started to introduce other faces into the public arena. Where once all public statements came from the mouth of Jim Allister, the TUV is now adopting the DUP's trick of sharing its press releases out between its active members.

On 25 June Ivor McConnell, TUV Chairman, put his name to a press release (ironically to complain about the Review Committee's trip to Dublin – Ivor sees this as evidence of "Dublin interference", yet was happy to put his name to another press release two days later which deals with an exclusively Dublin-related matter!)

TUV vice-chair Keith Harbinson had a go on 26 June.

TUV Secretary Karen Boal had her turn on 25 June.

In none of the press releases was the named 'releaser' actually related to the subject matter – it seems to just be a ploy to get their names (rather than just Allister's) mentioned in the press. All of these names are, of course, well known – Harbinson was the author of the DUP's first humbling in Dromore in February 2008 – but it still only adds up to four active members. The TUV will have to broaden out a lot more if it is to stand any chance of actually gaining seats either in Westminster or the Assembly. If it fails to do that, it will fall back into obscurity as a minor irritation for the other unionist parties.

The Power delusion

What kinds of powers would a real government and parliament have?

Well, it is often argued that fundamental purpose of government is the maintenance of basic security and public order. But the Northern Irish 'government' has no power whatsoever in these areas – although control of the police may soon be devolved, to date it has not been. The other branches of 'security'; military, intelligence, coastguard, border controls, and so on, will continue to remain strictly out of Northern Irish hands.

Other areas of government power usually include fiscal policy, economic policy, social security, healthcare, the environment and education. But in most of these the Executive has little or no power. It has no tax-raising powers at all, apart from setting a 'regional rate', and is entirely dependent on London for decisions on income tax, corporation tax, VAT, road taxes, and so on. It therefore lacks control over one of the most basic tools of economic policy.

Not only does it lack the power, but it also lacks responsibility. Northern Ireland receives from London a block grant that covers the majority of public expenditure (over 90%). No matter how well or badly Northern Ireland performs, that block grant does not vary significantly, so the Executive is not under any particular pressure to ensure that the economy is actually generating the revenue needed to finance its spending.

On the 'big-ticket' items like health, social welfare and education Executive Ministers have discretion to allocate the resources received according to their assessment of local needs and priorities, but the overall amount is nonetheless limited by the contribution from London. The Executive merely repositions the deckchairs – it cannot even decide how many there should be.

Overall, then, the picture is one of a 'government' that does not control its constitution, its defence, its internal security, its justice and legal systems, its broadcasting systems, its fiscal and economic policies or its foreign policies; it cannot make treaties or enter into international agreements; it has no separate or independent representation in the Council of the EU, nor does it have a European Commissioner, judges in the European Court, or members of some other EU bodies; and it is entirely subject to the control of another external authority (the British government). The overwhelming majority of its laws come from outside Northern Ireland – either from Brussels or from London.

This, then, is the 'power' that is being shared!

So what is it for? Why is there a 108 member Assembly, and a 12 member Executive, along with ridiculous numbers of staff, and obscene levels of expense, in order to basically tinker around the edges of health and education expenditure?

The simplistic answer (though not necessarily the wrong one) is that it is all part of a pay-off, designed to provide the key figures in each of the warring groups with positions of prestige and personal enrichment. This is the old-fashioned British approach to governing 'the colonies' – divide and buy off the natives. There is nothing that defuses resistance quicker than a pay-cheque and a ministerial limousine. Part of the sordid bribery of the natives is the construction of elaborate facades that mimic real power and authority but are essentially hollow. So it seems to be in Northern Ireland – the 'natives' are persuaded to accept their subordinate position by being given fancy titles ('First Minister', 'Minister for whatever', and so on) and inflated salaries. The British media, particularly the BBC, play along with the charade by giving inordinate airtime to these toy-town functionaries, and by helping to give the impression to the ordinary folk that the façade contains substance, when they know it doesn't.

A more cynical explanation (though this blog hopes it is the correct one) is that the charade is a deliberate training exercise. If the British and the unionists truly think that Northern Ireland will remain in the UK 'for the foreseeable future', then the only logical system of governance is direct rule. Setting up a play-government may, however, be a way in which the British are preparing Northern Ireland for what Britain knows is coming – withdrawal followed by Irish reunification. A generation of toy-town 'government' may ingrain in the powerless power-sharers at least an understanding of the processes of government, so that when they sit down with their fellow Irishmen and women to work out the structures of the new Irish state, they will at least be familiar with the language.

Sunday 28 June 2009

Orange Order withering away

In 1948 the number of Orangemen was 76,447; this rose to its highest number in 1968 – 93,447 members, but this fell to 64,160 within a year and has declined ever since. In 1990 it was claimed that there were 100,000 members in Ireland, but there were actually only 47,084.

By 2006, the latest year for which figures are available, the number of members was 35,758.

And yet they organise around 3,000 marches a year – almost one for every ten members! This must require every Orangeman attending multiple parades all through the summer. If nothing else, its good exercise, but surely hard to sustain in the modern era with many other calls on free time.

If the decline continues (as it surely must – the age of many marching Orangemen is visibly above average) then within a few years the Orange Order will be an irrelevant hang-over from the past, and wider society will probably tolerate its eccentricities in the same way as it tolerates the Salvation Army or vintage car enthusiasts. Then it can claim its rightful place in Ireland – the history book.

Friday 26 June 2009

Scotland

Scotland is also vital in so far as Northern Irish unionists (though not all) feel a sense of kinship with Scotland. Many carry Scottish names, many worship in churches that are to all extents and purposes Scottish, and some can even see Scotland on the horizon. Some, less sensitive to ridicule than most, even affect the wearing of Scottish-style kilts!

Would Scotland want Northern Ireland? Almost certainly not. Apart from the sheer cost of Northern Ireland – a state on welfare – there would be the issue of trying to persuade the 42% (and growing) minority that would prefer reunification with the south that their interests lie in an illogical federation. Scotland would not wish to embark on its nation-building with an awkward appendage across the Straits of Moyle.

Would England want to keep Northern Ireland? Would Northern Ireland really want to be England's scruffy back garden? It is likely that Scottish independence would kindle a parallel urge towards English nationalism, but whether this would lead to the formal dissolution of the UK is harder to predict. What is likely, though, is that the uncertainty would lead to a serious outflow of people to either Scotland or England, as those with ties to those places would not want to find themselves (or their assets) stranded in a post-breakup Northern Ireland. The demographic effects of a breakup of the UK might be sufficient to ensure that Northern Ireland votes comfortably for reunification with the south.

How likely is it that Scotland will vote for independence?

Support for, and opposition to, independence for Scotland is running about even at present: currently 39% say they would vote 'no' in a referendum, 38% would vote yes. The strength of the SNP is often considered as a proxy for 'independentist' support. In the recent European Parliament elections the SNP vote increased significantly, by 9.4% to 29.1%. This is clearly less than the majority that would be needed, but there are many labour or other voters who would, in a referendum, vote for independence.

The SNP also did exceptionally well in the 2007 election for the Scottish Parliament, increasing their share of the vote considerably both in the constituencies and regions (the system is a complex mixture of FPP in constituencies and the d'Hondt system in the regions). Whether the SNP's success is simply a result of Labour's unpopularity, or a genuine growth in support for independence, is hard to judge.

The SNP has a manifesto commitment to hold a referendum on independence by 2010, which the three 'English' parties are opposed to. Doubts exist over the legal and constitutional ability of the SNP to declare independence even if a referendum voted for it. But it is unlikely that the Westminster parliament would be so foolish as to deny Scotland the independence that it voted for.

The moves towards independence for Scotland are of considerable importance in Ireland, as Irish reunification would probably be a direct effect of Scotland's decision to collapse the UK. Even the debate around Scottish independence may have a positive impact if it forces some unionists into thinking about an uncertain future. The realisation that the UK may disappear from under their feet could spark some deeper reflection than normal.

Wednesday 24 June 2009

The DUP running scared

Jim Allister lost his European Parliament seat on June 4, but succeeded in humiliating the DUP by dislodging them from the top of the poll, allowing Sinn Féin to top the poll, and forcing Diane Dodds into an ignominious scramble for the last seat. He has publicly stated that he intends to stand in North Antrim at the next Westminster election as another direct challenge to the DUP.

It has been widely rumoured that Ian Paisley senior would retire at the next Westminster election, and hand over the DUP candidacy (and up to recently this meant handing the seat too) to his son, Ian Paisley junior. But clearly the DUP is seriously rattled by the TUV, who are out-flanking them on the unionist extremist side. By announcing that he will stand again, Paisley senior is effectively admitting that he (and the DUP) think that Allister would beat Paisley junior or any other DUP candidate. This clear admission of lack of confidence – even though the election is almost a year away – demonstrates that the DUP do not believe that they will be able to claw back much support from Allister and the TUV by then.

It appears that the DUP consider that the votes lost to the TUV are lost for a considerable time, if not for ever. If they are correct, the development throws the elections to Westminster (2010), the Assembly (2011) and the new Super-Councils (2011) wide open.

Update:

Jim Allister seems to agree with this blog's conclusions. In a press release today (24 June) he said:

"It is clear that the DUP have been panicked by Traditional Unionists and that the party lacks confidence in Ian Paisley Junior".

McGuinness's easy moral victory

"The days of republicans stretching ourselves and our communities to maintain calm in the face of sectarian provocation cannot last forever. It is now time for the issue of contested parades to be dealt with once and for all. That means the Orange Order making its contribution to peace. It means a declaration from the Orange Order that, in future, it will no longer seek to force parades through Catholic areas and risk bringing violence on to our streets."

Predictably, the Orange Order responded in knee-jerk style, saying that McGuinness's comments were "a disappointing attack on the Protestant community. For years, Sinn Fein policy has been to make life as difficult as possible for parade organisers. They have totally failed to understand that parading is an integral part of the Protestant culture."

Unionist politicians weighed in on the Orange Order's side too:

The DUP said that "the comments by Martin McGuinness are an abdication of leadership by Sinn Fein on the parades issue".

The TUV saw "the comments made by Joint First Minister Martin McGuiness in respect of Orange Order Parades as inflammatory, provocative and extremely misguided" and "amount to little more than a cloaked threat against the outcome and safety of parades involving law abiding men, women and children taking part in lawful public processions to and from Christian Worship".

(The UUP officially made no statement.)

While all of this is depressingly predictable, within Northern Ireland at least, on the wider stage it represents a significant and subtle victory for Sinn Féin.

The London Independent newspaper, one of the very few non-Irish papers to carry the story, started their report as follows:

"The Orange Order was today challenged to make a contribution to the peace process by stopping attempts to march through Catholic areas. Northern Ireland Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness said that while the IRA, loyalists, political parties and governments have made significant steps forward over 15 years, the Orange Order has refused to budge."

The immediate impression given is that McGuinness requested to Orange Order to 'contribute to peace' but the Order churlishly 'refused to budge'.

But the icing on the cake for Sinn Féin, and the factor that swung the story strongly in their favour, were the attacks on the Roma people in south Belfast that dominated reporting of Northern Ireland over the weekend. Martin McGuinness came out strongly to condemn the attacks, and was widely reported in both print and broadcast media. His was the 'official' voice of Northern Ireland seen on the BBC's main television news (beamed worldwide on BBC World), and he stood in direct opposition to the racism and thuggery of the attackers.

After several days in the spotlight McGuinness has emerged as a caring anti-racist mature politician. No mention was made of his IRA past, as if that is ancient history.

His appeal to the Orange Order will be seen in that light – a genuine request by a caring mature anti-sectarian politician to an organisation that is 'refusing to budge'. The easy conflation of the position of the Orange Order – a flag-waving group of reactionaries – with that of the south Belfast racists – reportedly linked to another group of flag-waving reactionaries (Combat 18) – has left McGuinness with an easy moral victory.

The Orange Order can snarl and huff about how nobody appreciates their traditions, but the damage has been done and world opinion, in so far as it notices or cares, will have moved another notch or two away from supporting them. The Orange Order failed to understand the media importance of the events in Belfast, and how they were providing Martin McGuinness with a worldwide audience. Instead of responding imaginatively and intelligently, the Orange Order attacked the man who was standing up to racism, and thereby placed themselves in the camp of the racists.

Tuesday 23 June 2009

Partition and repartition, part 6: some modest proposals

The issues of religion and politics are often conflated when discussing Northern Ireland, and hence many proposals on repartition assume that the new borders should be based on religious identity. This blog disagrees. While religion of course does play an important role in peoples political identity, only the expression of that political identity should inform public policy.

A point that needs to be made is that although to most people the word 'repartition' means re-setting the borders between two sovereign states, this does not have to be the case. All borders – internal or external – can be seen as a form of partition. Federal countries like Spain or Belgium have internal borders, which in many respects represent partition lines between linguistic or 'ethnic' groups. Discussion of repartition in the Northern Irish context can go hand-in-hand with discussion of a united Ireland, or even with discussions of continued union with Britain.

In other words, even in a united Ireland it is valid to examine whether some areas should have a different status, which areas those should be, and what nature of different status these areas might have. Although the present Republic is a unitary state with almost all power emanating from Dublin, this may not be the best model for a united Ireland. It may be appropriate, sensible and democratic to devolve some powers to lower level authorities. Some powers are highly territorial and would require defined boundaries within which to operate – taxation, regional policies, police divisions, etc; while others can non-territorial – education, or broadcasting. The example of Belgium, though complicated, is very interesting in this regard. Belgium has both geographically defined regions (three) and linguistically defined 'communities' (also three), but their borders are not the same. Brussels, a region for matters of taxation, administration, and so on, runs no schools. They are the responsibility of the communities (French-speaking and Flemish-speaking), who run separate parallel systems in Brussels. In the Northern Irish context such a system could allow, for instance, education, culture and broadcasting to be separated according to 'community' while roads, water supply, planning, etc, are handled by regional authorities defined by strict geographic boundaries. Thus, parallel to a small 'unionist' region in east Ulster, there could be a 'Protestant' education authority responsible for all the Protestant education in the whole of Ireland, a nation-wide Protestant/Unionist-tinted broadcaster, an Ulster-Scots cultural body with powers, grants, cultural centres, etc, across the whole of Ulster (and further?).

For reasons of security, community confidence, etc, it may be appropriate to have a separate police force in 'unionist' areas, while the Garda Síochána polices the rest of the country. For such a thing to happen, though, the limits of such a unionist area would need to be established.

There are several possible models for defining the boundaries of a 'unionist' region in a post-unification Ireland, including:

A. Cantonisation

Depending on the types of powers devolved to sub-regional areas, the semi-autonomous areas can be quite small. Clearly a small region cannot have responsibility for building motorways or railways, but it could run many of the personal services that are visible and important to the people. By entering into cooperation agreements with other similar areas it could achieve significant economies of scale.

Where areas display a clear preference for one or another political direction, this could be facilitated by the creation of a myriad of cantons or different sizes and shapes. These would not be hermetically sealed – quite the opposite – but they would allow the inhabitants of the areas to have certain services provided by authorities in whom they have confidence, and would allow certain rules and laws to reflect their ethos.

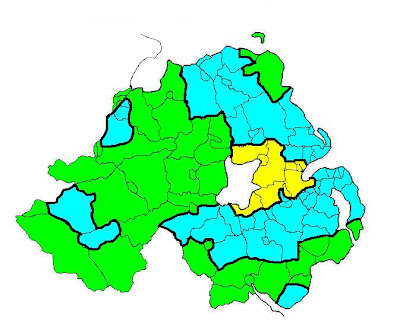

A cantonised Northern Ireland, based loosely on the outcome of the 2005 local elections, could look like this:

B. Larger and more powerful regional bodies

If the powers to be devolved were of a wider nature, requiring more powerful local authorities (or simply a more numerous population to make them cost-effective), then Northern Ireland could be re-partitioned according to the 'colour' of the current local authorities as recorded in 2005:

Another way of drawing a boundary could be to look at the expressed political preference by District Electoral Area (DEA), while striving to retain contiguity:

C. Belfast

In the options described above Belfast has been deliberately excluded. It is big enough to form a region in its own right, or, in a cantonised approach, several sub-regions. However, it makes no sense to try to sub-divide the running of a large city. Already Belfast is artificially limited for political reasons – it makes more sense to expand its boundaries to allow its services: transport, waste, housing, etc, to cover all of those living in its metropolitan area.

One way to do this, while correcting the anomalies of Loughside (in Craigavon) and Antrim North-West, both nationalist areas creeping around Lough Neagh to join up to Belfast, is to create a central 'neutral' region comprising Belfast, and these areas, which acts as a bridge between the 'unionist' areas to the south and north of Belfast, and to the larger 'nationalist' Ireland to the west. This neutral region could be governed either through power-sharing, or through a strictly balanced council, appointed by the two communities. It would include Belfast port and both airports, and could become a genuine city for all the people of east Ulster.

The map blow shows how a neutral Belfast region could fit into a cantonised model:

The models presented above could amount to a confederal Ireland. There are no practical difficulties in implementing such an outcome, and indeed very few political difficulties for nationalists. With the country at peace, and being a Member State of the EU with all of the freedoms of movement, trade and opinion that this ensures, a repartition into semi-autonomous areas could provide both security, opportunity, and pride to all of the people of Northern Ireland. Combining geographical repartition with non-territorial authorities for 'community' issues could ensure an even greater level of satisfaction.

The models presented above could amount to a confederal Ireland. There are no practical difficulties in implementing such an outcome, and indeed very few political difficulties for nationalists. With the country at peace, and being a Member State of the EU with all of the freedoms of movement, trade and opinion that this ensures, a repartition into semi-autonomous areas could provide both security, opportunity, and pride to all of the people of Northern Ireland. Combining geographical repartition with non-territorial authorities for 'community' issues could ensure an even greater level of satisfaction.Far from being a taboo subject, repartition is a subject that needs to be discussed. No realistic planning for a post-reunification Ireland can avoid it.

Partition and repartition, part 5: the current situation

Observant readers may have noticed that most of the suggestions for repartition refer to Protestants and Catholics, rather than unionists and nationalists. This blog has repeated those terms, but does not support their use. While there is a great coincidence between Catholicism and nationalism and between Protestantism and unionism, the only correct criteria to judge people’s political preferences are political criteria. Thus only how people vote should count as a guide to political decision-making, not how they pray.

Having said that, though, it may be instructive to look at how wrong and inaccurate a repartition model based upon religion would have turned out to be. Previous blogs have shown the rough religious maps that were (mis-)used to argue for different border proposals:

The British in 1972:

The UDA in 1994:

The map below is based on the results of the 2001 census, and shows clearly that neither of the earlier maps was accurate or fair.

In a simplified form (below), it looks quite similar to the Kennedy/UDA map, though the Kennedy/UDA map tends to be rather more 'generous' to the 'British Ulster' territory, giving it almost all of the Protestant territory, the Catholic enclaves within Protestant territory, and 'bridges' to connect up the Protestant bits.

There is a trick contained in the detailed map, as well. Areas that are less than 50% Catholic are coloured orange, giving the impression that they are majority Protestant – which may not be the case. Some of the ‘non-Catholics’ may in fact be cultural Catholics (or nationalist voters) who are post-religious. Gortin (just north of Omagh), for example, has a Catholic population slightly less than 50%, but a Protestant population that is smaller, at 44%. Yet it shows as a light orange colour! Other areas follow this pattern, giving a slightly misleading impression of 'unionism's' territory.

A more democratic method than religion is political expression.

The smallest area for which we have detailed voting records are the District Electoral Areas (DEAs) used to elect councillors to the District Councils. There are 101 DEAs, all designed to contain comparable numbers of electors (though there is considerable variation).

The map below shows the DEAs in which unionist parties and independents of all stripes received over 50% of the vote in the most recent local elections (2005):

Although there is some similarity between this and the ‘religion’ map, certain areas that appear to be ‘Protestant’ turn out not to be unionist – Cookstown, Magherafelt, Enniskillen, Omagh.

The map below shows the DEAs in which Nationalist parties and independents received over 50% of the vote in 2005:

This blog is about repartition, so the maps should be looked at in this light. Clearly any proposal to re-draw Northern Ireland’s borders should be guided by several basic principles:

- The errors of the old partition should not be repeated

- As far as possible both groups should find themselves in the territory of their choice

- ‘Islands’ must be avoided, especially where they lack any large population centre to give them any chance of economic or demographic survival

- The territories should be contiguous, or in the case of the ‘nationalist’ part(s) contiguous with the south, with which they would unite.

As ever, the true problem in any repartition proposal is Belfast. Roughly balanced, but becoming rapidly more Catholic and nationalist, it is sitting like a baby Cuckoo in the centre of unionist east Ulster. Its sheer numerical importance means that it cannot be ignored, but its location makes it very difficult to imagine a repartition model that can deal with it fairly and rationally.

Although it is not the intention of this blog to promote repartition, the next and final part of this series will look at several options for the re-partition of Northern Ireland, including at least one that aims to deal with the problem of Belfast.

[Next post: some modest proposals]

Monday 22 June 2009

Partition and repartition, part 4: the UDA's Doomsday Plan

Despite the bravado of the UDA and other loyalist terrorists about 'Ulster', it is clear that they considered that around half of Northern Ireland was 'lost'. Their document stated that "British military intelligence suggests that at least two and probably three counties in Ulster are already lost. Surrendering two or three counties to the Irish Republic would alleviate much of the security problem". One assumes that these two or three counties were in addition to the three Ulster counties that had already been 'surrendered' in 1921?

The UDA's intentions for the Catholic population left in their new, truncated, Northern Ireland were sinister. The Catholic population left on the 'Protestant' side of the Orange Line was to be "expelled, nullified or interned". 'Nullification' was a euphemism for massacre. Those 'interned' were to be used, effectively, as hostages or 'useful bargaining chips' in possible negotiations.

The UDA's document was published in the Sunday Independent newspaper in 1994, unfortunately just before the internet started to provide an accessible archive, so while the document itself remains out of reach to this blog, its theoretical underpinnings do not.

The Orange Line that the UDA hoped to draw across Northern Ireland was based on the work of Liam Kennedy, author of the 1986 book Two Ulsters; A Case for Repartition. Although Kennedy was reportedly unhappy about the UDA's use of his work, others were less unhappy. Sammy Wilson, currently a DUP MP, Belfast City councillor and from today, Minister of Finance in the Northern Ireland Executive described the UDA's plans for mass murder and ethnic cleansing as a "very valuable return to reality" and that it showed "that some loyalist paramilitaries are looking ahead and contemplating what needs to be done to maintain our separate Ulster identity". Slobodan Milosevic and Radovan Karadzic would, no doubt agree, but unfortunately for the DUP such things are defined as crimes against humanity under the statutes of both International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

The map that Liam Kennedy suggested, and that the UDA adopted, was this one:

It includes three categories of area: (1) the core 'British Ulster' area, (2) an extension down the east bank of the Foyle and as far as Omagh, and (3) an island of Protestant majority territory in Fermanagh.

Clearly these boundaries could not have been used as viable boundaries for a besieged people. To hold even the 'core' area would be a serious challenge without some adjustments – there are too many corridors and near-enclaves. But of course the UDA may have hoped to resolve these by their preferred means – mass murder.

The Bosnian war showed that, eventually, the world would not accept mass murder and ethnic cleansing. If this was true in a region of south-eastern Europe without many ties to the US (who were the ones who acted against the Serbs after years of European dithering), imagine how deafening the calls from Irish-America would have been if the UDA were to try something similar in Ireland? The UDA would have found themselves at the receiving end of the US Airforce, and their leaders would have found themselves in front of the International Criminal Court in the Hague accused of war crimes.

[Next post: the current situation]

Sunday 21 June 2009

Partition and repartition, part 3: 1972

The violence that broke out at the end of the 1960s reached its high point in 1972, though of course at that time nobody knew that the number of deaths would peak in that year and then decline. It seemed in 1972 as if Northern Ireland was going to be consumed in an inferno of bombs, bullets, riots and societal breakdown. Stormont was prorogued (suspended) to the consternation of unionism, and the world watched aghast as Britain sent paratroopers to slaughter peaceful protesters in Derry.

As so often in relation to Ireland, the British government played a two-faced game. On one hand, following the Darlington Conference in September 1972, it published a discussion paper a discussion paper The Future of Northern Ireland: A Paper for Discussion, in which it stated, in relation to repartition:

"It has been argued that consideration might be given to a partial or incomplete transfer of sovereignty either in geographical terms (ie by transferring to the Irish Republic those parts of Northern Ireland where a majority in favour of such a transfer exists) or in jurisdictional terms (eg, by adopting a pattern of joint sovereign responsibility for Northern Ireland as recommended by the Social Democratic and Labour Party or by a scheme of condominium for which there are such precedents as the New Hebrides and Andorra). However neither of these courses if adopted without consent, would be compatible with the express wording of Section 1(2) of the Ireland Act, 1949. Moreover the exponents of a united Ireland all demand a unity of the whole island and show no sign of settling for less: they might well regard the establishment of a predominantly Protestant state as an obstacle to unity."

But on the other hand the British government secretly planned for the repartition of Northern Ireland in the case of uncontrollable violence – though the plan was rejected as unworkable.

Papers released under the 30-year-rule revealed that the British government considered moving hundreds of thousands of Catholics if they could not stop the worsening sectarian violence.

"Prime Minister Heath was presented with a series of options including a 10-page paper called "Redrawing the border and population transfer".

It looked at whether republican violence could be stopped by:

- Transferring areas with a Catholic majority to the Republic of Ireland

- Moving individual Catholic families to the Republic of Ireland

The authors drew up maps of how it could work - only to find the areas identified for transfer included huge numbers of Protestants.

"To transfer the whole of the territory west of the River Bann would put 238,000 Catholics and 227,000 Protestants into the Republic," the report said.

In addition, the authors admitted they had no idea how population transfer could be applied to the majority of Catholics living in Belfast or other urban areas."

The plans contained maps showing both the areas that the British considered to have Catholic majorities:

On the basis of this map they went on to prepare a ‘simplified’ map showing the areas to be ceded to the south, along with an estimate of the Protestant and Catholic populations effected. The maps below are taken from the BBC and may not accurately represent the proposals:

The statistics that the plan’s drafters used are unknown, but presumably included the 1971 census – widely boycotted – and recent election results. There are some anomalies in the analysis:

- It shows areas like Cookstown as having a ‘large Catholic population’, despite the fact that in the early 1970s the district had a distinct unionist majority: 56.6% in 1973. Cookstown district only fell into nationalist hands in 1997.

- It planned to include Castlederg in the reduced Northern Ireland, but not the neighbouring – and much more strongly unionist – north Fermanagh, an area that still today has a unionist majority.

- It bizarrely shows Crossmaglen as being in ‘Protestant’ territory, though sensibly planned to hand it, and the whole of South Armagh, to the republic.

- It shows the strongly nationalist Crossmore DEA in Armagh as being ‘Protestant’ and planned to keep it in the reduced Northern Ireland – perhaps to provide a bridge to Aughnacloy and the Clogher Valley, though these areas it also planned to cede to the south, despite their then unionist majority.

Had the repartition considered by the British government in 1972 come to pass it would have created as many problems as it hoped to resolve. Localised unionist majorities in north Fermanagh and Cookstown would have found themselves ‘behind enemy lines’, while the nationalists of Crossmore would have found themselves still in Northern Ireland despite being surrounded on three sides by the Republic. There would have been a long and unnecessary strip of ‘Northern Ireland’ stretching down the east bank of the Foyle to Castlederg (and including Strabane!) for no sensible reason.

The 1972 plan was perhaps a good example of why Northern Ireland is never very well managed by the British – they appear to get simple facts wrong, despite their potentially lethal consequences.

[Next post: the UDA’s Doomsday Plan]

Friday 19 June 2009

Partition and repartition, part 2: the Boundary Commission

In support of its belief that these ideas would not be insignificant, it further stated that "The Parliament of 'Northern Ireland' was opened on the 22nd day of June, 1921, but 12 members elected for constituencies in 'Northern Ireland' refused to recognise the jurisdiction of that Parliament, and never participated in any of its functions. The said 12 members were distributed as follows:- namely, 4 were elected for the Counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone, 2 for the County of Armagh, 1 for the County of Antrim, 1 for West Belfast, 2 for the County of Down, and 2 for the County of Londonderry (including the Borough of Londonderry)." These members represented half of the 8 members of the NI Parliament from Fermanagh and Tyrone, half of the 4 members for Armagh, 1 of the seven for Antrim, 1 of the four for West Belfast, a quarter of those from County Down, and 2 of the five from Derry.

The Free State government expected, quite reasonably, that large areas of south Armagh, south Down, Fermanagh, Tyrone and Derry would be transferred to the Free State by the Boundary Commission.

However, the work of the Commission was wrecked, largely on account of the premature publication of its findings (including the map below) in The Morning Post on 7 November 1924. This showed that the Commission did not, in fact, propose the kind of large-scale transfers of territory that the Irish Free State had expected. The Commission, with a built-in British-Unionist majority, voted to leave the provisional border untouched, and in a sordid little deal the Dublin government acquiesced. The border, provisional, unpopular, incorrect, inefficient and unfair, has remained petrified ever since.

The work of the Boundary Commission remains controversial to this day. Its report was suppressed until 1968, and when released revealed a number of curious elements:

- It made the decision to retain the Mourne Mountains within Northern Ireland because of the location of the Belfast Waterworks and sources of water there, although the region had a clear Catholic majority,

- the Irish government anticipated large transfers of territory, chiefly at the expense of the six counties, but the British government looked only for minor adjustments. The Commission treated the existing boundary as the default unless there were convincing local reasons for adjustment.

- it defined a zone on either side of the six counties boundary, varying from a few yards to 16 miles from the existing boundary in which they conducted their detailed investigations and took evidence from witnesses. They clearly did not plan to make changes outside this frontier zone, despite the large nationalist areas 'inland' from the border.

- it concluded that changes could only be made were the majority was a “high proportion” of the inhabitants of the district concerned. No figure was given, but typically in areas proposed for transfer to Northern Ireland on the grounds of a Non-Catholic majority, the percentages are 63 to 66% of Non-Catholics in the total population, whereas in areas proposed for transfer to the Irish Free State the proportion of Catholics in the total population is typically much higher, from 79 to 93%. It seems that the Commission was operating according to double standards.

Nationalist Ireland was, and remains, scandalised by what it considered to be treachery – it had been tricked into a border that it felt disadvantaged it considerably and locked hundreds of thousands of nationalists into a state that was mutating into a 'Protestant state for a Protestant people'. Northern nationalists, in particular, felt abandoned and betrayed.

On one level, northern nationalists were betrayed – displaying a Machiavellian approach to the border, the Free State's Minister for Justice and External Affairs, Kevin O'Higgins, is reported to have written that "... the Boundary Commission at any time was a wonderful piece of constructive statesmanship, the shoving up of a line, four, five or ten miles, leaving the Nationalists north of that line in a smaller minority than is at present the case, leaving the pull towards union, the pull towards the south, smaller and weaker than is at present the case." Although this quotation is unconfirmed, it represents a line of thought that is still common today – that a re-partition leading to a smaller but more unionist Northern Ireland would make the eventual re-unification of Ireland harder. Better, for some people, that the minority of dissatisfied northern nationalists is as large as possible.

Despite the sense of betrayal, and sporadic campaigns by nationalist Ireland including the Dublin government to remove the border, no further serious proposals to re-draw the boundaries of Northern Ireland were made for another two generations. That was to change in the 1970s when the upsurge of violence and civil unrest made an increasing number of people, both in the British government and in the ranks of unionism and loyalism, question whether Northern Ireland could remain viable within its current borders.

[Next post: 1972]

Partition and repartition, part 1

Though this blog considers the partition of Ireland to have been wrong – democratically, culturally, economically, socially … in every respect, in fact – and considers that a further repartition is not the solution to the problems created by partition, the continuing interest in the topic means that it deserves at least to be discussed.

Over the next week or so this blog will look at some of the proposals that have been made, and will try to assess them dispassionately. First, though, it is useful to remind ourselves of how the situation arose in the first place.

Almost before the ink was dry on the 1800 Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland nationalists started working towards its repeal. For reasons that are still debated, the earlier support amongst northern Presbyterians for the United Irishmen disappeared, to be replaced by strong support amongst most northern Protestants, for the Union with Britain. This started to pose problems for the growing Home Rule movement when they strongly opposed it, and opted for continuing close ties with Britain.

Home Rule

The various Home Rule bills came and went, with the First World War intervening at a crucial time in the passage into law of the 1914 Government of Ireland Act, which would have led to devolution for the whole of Ireland. The Act was suspended, and then overtaken by evens – the 1916 Easter Rising, the 1918 Election, the War of Independence, before being replaced by the new Government of Ireland Act of 1920.

The Rising, the election, and the War of Independence led the British to conclude that the 1914 Act was inadequate. The 1916 Rising, though a seminal event for nationalism, probably had a negative effect on the prospects of northern unionists acquiescing to Home Rule. The 1918 election, on the other hand, demonstrated clearly that the desire for autonomy in Ireland was strong and shared by the majority of the voters. Including the uncontested constituencies (25 of the 105), it is estimated that the Sinn Féin share of the vote would have been around 53%, with an additional 22% going to the Irish Nationalist Party and other nationalists. Sinn Féin alone won 73 of the 105 seats, thus giving it, under the British system used for this election, an overwhelming majority.

Government of Ireland Act, 1920

Two attempts were made by the British Prime Minister Asquith during the First World War to implement the Home Rule Act, first in May 1916 which failed, then again in 1917 with the calling of the Irish Convention which led to a cabinet Committee for Ireland, under the chairmanship of former Ulster Unionist Party leader Walter Long, who pushed for a radical new idea – the creation of two Irish home rule entities, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland with unicameral parliaments. The House of Lords amended the old 1914 Bill accordingly, to create a new Act with two bicameral parliaments, "consisting of His Majesty, the Senate of (Northern or Southern) Ireland, and the House of Commons of (Northern or Southern) Ireland", in an essentially confederal Ireland. Northern Ireland was defined for the purposes of this act as "the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry …" The Act saw both parts of Ireland having identical arrangements with an overarching Council of Ireland.

The choice of counties to include in the new Northern Ireland seems to have depended mainly upon the areas that the unionist leaders felt that they could dominate and control. While the 1912 Covenant referred only to 'Ulster', it soon became clear that unionism would not have a majority in the whole province. In the 1918 election unionist candidates got 58% of the votes in 9-county Ulster, with nationalists getting 39%, but this underestimates nationalist support, as Sinn Féin were returned unopposed in both Cavan constituencies. If an estimate is made of their support there, the nationalist minority would be over 41%. Unionist leaders were concerned that they would have trouble dominating such a large minority, and opted rather for a smaller, more manageable 6-county state, excluding the three counties with large nationalist majorities. This gave them a 66%-31% majority. The fact that their chosen counties contained large numbers of nationalists did not concern them hugely – their aim was to retain as many unionists within their territory as possible.

The Treaty

The Treaty between Britain and the Sinn Féin leadership in Ireland that ended the War of Independence went further, and while it allowed for the creation of an Irish Free State, it permitted the Northern Parliament to opt out of it:

11. Until the expiration of one month from the passing of the Act of Parliament for the ratification of this instrument, the powers of the Parliament and the Government of the Irish Free State shall not be exercisable as respects Northern Ireland, and the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, shall, so far as they relate to Northern Ireland remain of full force and effect, and no election shall be held for the return of members to serve in the Parliament of the Irish Free State for constituencies in Northern Ireland, unless a resolution is passed by both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in favour of the holding of such elections before the end of the said month.

12. If before the expiration of the said month, an address is presented to His Majesty by both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland to that effect, the powers of the Parliament and the Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland, and the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, (including those relating to the Council of Ireland) shall so far as they relate to Northern Ireland, continue to be of full force and effect, and this instrument shall have effect subject to the necessary modifications.

Needless to say, the unionist-dominated Parliament of Northern Ireland presented the necessary 'address', and the 1920 Government of Ireland Act remained in force as the Constitution of Northern Ireland until its repeal in 1999. The subtle text of the Treaty also replaced the Council of Ireland with an umbrella authority by the Free State over the north (the Free State would, in effect, have the powers that the Council would have had). Needless to say, this contributed to unionist resistance, and once the 'address' was made these overarching powers disappeared, and the Council of Ireland with it.

So by a series of legislative manoeuvres, assisted by the military weakness of the IRA, the military strength of Britain, and the geographic concentration of unionists in north-east Ulster, Ireland was now effectively partitioned. All that remained was to fix the border. Although the Government of Ireland Act specified the six counties as constituting Northern Ireland, the Treaty (Article 12) went on to say that:

Provided that if such an address is so presented a Commission consisting of three persons, one to be appointed by the Government of the Irish Free State, one to be appointed by the Government of Northern Ireland, and one who shall be Chairman to be appointed by the British Government shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland, and for the purposes of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, and of this instrument, the boundary of Northern Ireland shall be such as may be determined by such Commission.

[Next post: The Boundary Commission]

Wednesday 17 June 2009

Jim Allister, friend of nationalism

Today he is quoted in the News Letter as hoping to "topple power-sharing by using a boycott plan that would likely see a nationalist majority in a Sinn Fein-led Executive. This would be intolerable to most unionists, and might scupper the prospect of republican-led rule of the Province"

Thanks to the effects of proportional representation, the TUV could get enough seats to ensure that a boycott by them of the Assembly could mean unionists are in the minority in the Executive. If this meant that Martin McGuinness would become First Minister and unionists would be minority in the Executive, Allister hopes that the Executive would "implode" because it would be 'unrepresentative of unionism'.

Such is Allister's hatred of nationalists that he would rather contemplate the destruction of Northern Ireland's political institutions than countenance an entirely imaginary 'dominance' by them. There is, in practical and administrative terms, no difference between Martin McGuiness as deputy First Minister and Martin McGuinness as First Minister. The two posts are equal in weight and power.

Allister's plan rests on several assumptions:

Firstly he assumes that the other unionists share his visceral hatred of nationalism. While some of them are certainly no fans of nationalism, the fact that they are currently operating the power-sharing institutions shows that they are not as extreme as he is. His plan would require the UUP also to walk away from the Executive just because there is a nationalist First Minister. Does he really think that they are as bigoted as he is?

Secondly, he assumes that the 'implosion' of the Executive would be, on balance, a good thing for unionism. But what would replace it? In all likelihood it would be replaced by Direct Rule with enhanced Dublin input – in practice, joint sovereignty. This is what happened the last time, and there is no reason to believe that it would not happen again. How, in Allister's tortured mind, could he see rule by part-time outsiders doing a stint in the NIO as a stepping stone in their careers to be preferable to locally answerable politicians taking responsibility for local affairs? And how, if the Dublin input is large and visible, could he square that with his wish to stop nationalists from exercising power?

The DUP entered the power-sharing arrangements because they were shown the alternative – the secret Plan B. Before this, they were almost as implacably opposed to power-sharing as Allister is now, but one threat of Plan B brought them to the table, and the chuckling began. Plan B has not gone away, of course, and despite its obvious lack of attraction for the DUP, Allister is threatening to reawaken it. Does he really know what he is doing?

Plan B is clearly much more 'green' than power-sharing, so is Allister playing with fire? If he has his way, and the Executive 'implodes' with unknown consequences, one of which may well be Plan B, Allister may turn out to have been a greater friend of nationalism than of unionism.

European Parliament election wrap-up

After running stories on the EP election since February 4 it is now time to wrap it up and look forward to the next election, for Westminster.

Before leaving the EP behind though, it is interesting to note that almost all of what this blog wrote in February came to pass, with the exception of Jim Allister's performance, which was much better than expected.

In February this blog wrote that:

"The breakdown of the vote in June's European Parliament election between the unionist block and the nationalist block will probably not differ much from the breakdown in other elections" – and in fact the outcome was almost indistinguishable from the 2004 EP election.

" … the relative strengths of the two blocks are approximately: Unionist 50%, Nationalist 43%" – and the outcome was 49% unionist, 42.2% nationalist.

" … this should translate again into two unionist seats and one nationalist seat" – not such a brave prediction, but nonetheless true.

"… Jim Allister, by sheer persistence and good timing, has managed to remain a serous threat to the DUP. While few expect him to hold his seat, the DUP are concerned that he will steal their more extremist voters and consign them to an ignominious scramble for the third seat" – which is exactly what happened!

" … The DUP may then suffer the double indignity of failing to keep Sinn Féin from topping the poll and having to depend on transfers from minor party candidates, which might not come. When the DUP candidate is eventually elected, he or she may have lost considerable face in the process" – exactly as came to pass.

" … The SDLP vote should hold steady" – and indeed, after dropping from 28% in 1999 to 16% in 2004, it remained almost unchanged at 16.2% in 2009.

" … Historically the 'Alliance and other' vote has tended to be around 8-9% in EP elections, and this time should be no different" – it was, in fact, 8.8% - exactly in the range predicted (though the Green portion was higher than this blog expected – 3.3% instead of 1%).

Enough blowing of our own trumpet. There were other sources of soft predictions, including the bookies. Northern Ireland has no reliable polls for most elections, so this blog relied heavily on the odds quoted by the bookies, particularly Paddy Power. And the outcome that those odds pointed towards was almost perfectly correct. The bookies predicted victory for the three candidates who won, and predicted correctly that Bairbre de Brún would top the poll. On the unpredictable performance of Jim Allister the bookies called it correctly – as polling day approached, they were quoting their shortest odds (i.e. representing what they thought was most likely) for a vote above 60,000 – and he scored 66,197.

As Allister's odds shortened, Dodd's lengthened, and that turned out to be exactly how the vote fell – Allister's votes appeared to have come entirely at Dodds' expense.

The lesson that this blog has learned is that, in the absence of reliable polling, the best predictor for the outcome of an election is how people are prepared to risk their cash. This lesson will be applied, of course, during the next election campaign – which should be starting very soon.

Tuesday 16 June 2009

A8 migration and its impact

NISRA has produced some useful data that should help us to sort fact from fiction. Although the study looks at 2007 figures, they are probably accurate enough even in 2009, though the recession may have reduced the numbers somewhat.

Precise figures on migration are difficult to find, so NISRA has used a variety of sources; GP registration, worker registration system, National Insurance applications, the Schools Census, and birth registrations. The result is an estimate of the size of the A8 population in Northern Ireland of "30,000 people of A8 origin living in Northern Ireland around December 2007".

Few of these 30,000 were in Northern Ireland in 2001 when the last census was carried out, so their impact on the Catholic-Protestant balance has not been properly recorded. But although mostly Catholic, most A8 migrants are not Irish Catholics and thus may not vote (if they vote at all) in the way that Irish Catholics tend to (i.e. for nationalist parties). This has allowed some unionists to fantasise about their impact – that they may side with unionism, that their numbers will keep growing and thereby swamp nationalist dreams of outnumbering unionists, and so on.

Do the facts provide any support for such fantasies, though?

Firstly, will the children of the A8 migrants help to tip the balance back in unionism's favour? Unionists assume that A8 migrants would all vote for unionist parties, though there is no evidence for this. It is more likely that they would not vote at all, or that they would vote in accordance with the ethos of the communities in which they live. Since the greatest concentrations of A8 migrants outside Belfast are found in Dungannon, Craigavon, and Newry and Mourne, it is likely that they will vote for candidates that have a possibility of helping them, rather than parties of perpetual opposition. Hence, nationalist parties ae just as likely to receive their vote as unionist parties. And once absorbed into nationalist communities and voting for nationalist parties, will A8 migrants and their descendents vote unionist in a border poll?

Even if the descendents of A8 migrants vote unionist in the border poll of the future, will they sway the result?

Currently, around 4,000 of the 30,000 A8 population are school-age children. But Catholic kids outnumber Protestant kids in the Schools Census by at least 30,000, so even if all 4,000 A8 kids were to grow up to be 'Polish Catholic Unionists' they could not save the unionist project.

The other leg upon which unionism rests its hopes is that the A8 migrants are actually responsible for the apparent difference in community birth rates, and that once they are taken out of the equation Catholic birth rates are no higher than Protestant birth rates.

If the assumption is made that A8 births are distributed in the same way as the A8 population, the A8 births can easily be estimated by Council areas, and then both they and the A8 population can be removed from the overall figures. The table below gives the result, as the number of non-A8 births per 1,000 of the non-A8 population in 2007. It shows that, even without the effect of A8 births, two types of districts have a birth rate that exceeds the average; some outer Belfast commuter areas, and majority nationalist areas.

Despite overall Protestant majorities, both Craigavon and Armagh are evenly balanced at child-bearing ages, and both have a majority of Catholics amongst their children. Antrim, though still majority Protestant at child-bearing age nonetheless has an equal number of Catholic and Protestant children.

The table shows that the majority-nationalist, or balanced, districts are towards the higher end of the birth rate spectrum, while the whole of the lower end is taken up by seven majority-unionist districts. Only the commuter-belt areas of Antrim, Lisburn and Banbridge offer unionism any hope, and even in these three there are considerable numbers of Catholic birth. It seems that indigenous Catholics are still having proportionately more babies than indigenous Protestants.

So, many of unionism's hopes for the impact of A8 migration are not going to happen. They are not going to become king-makers in a balanced Northern Ireland, and their births are not, in fact, masking a serious decline in Irish Catholic births. Unionism's last hope, that the children of A8 migrants will grow up to vote unionist, remains to be tested – but there is no reason to expect that it too will not ultimately be dashed.

Monday 15 June 2009

Brendan O'Leary and the prospects for a United Ireland

Hence it is inevitable that the speech made by Professor Brendan O'Leary at the Unite Ireland conference in New York on 13 June will be book-marked by unionists and repeated ad nauseam as if it were gospel.

O'Leary – soon to be beatified by unionists – "dismissed the argument that the nationalist population can out breed the unionists, though he did point out that the gap has closed significantly". His precise arguments are not revealed, so it is unfortunately not easy to counter them, but there is adequate evidence on this blog alone to question whether he is correct.

He also said that "it might make sense to preserve Northern Ireland as a unit and leave the South to decide whether it wishes to disaggregate into two or three units or just to have a two-unit federation. This, to my mind, is consistent with the principle of pluralism rather than assimilation." These are, of course, not new suggestions – many people have put forward possible structures for a post-reunification Ireland.

In essence, of course, O'Leary was arguing for the debate on reunification to move beyond the sectarian headcount. In order to try to move it there, though, he is trying to discourage those who count heads by telling them that that method will not work. This is also an old trick, one that was practiced for years by such eminent (but mistaken) thinkers as Garret Fitzgerald. In trying to move beyond head-counting into persuasion O'Leary has a very valid point, but it is a shame he muddied his argument by misrepresenting the demographic evidence.

It is the strongly-held opinion of this blogger that the best path to a united Ireland is through the identification of a majority of the population of Northern Ireland with the island as a whole – culturally, politically, historically, economically and socially. If that majority identification happens to come about through demographic changes, then it is just as valid a majority as if it came about through persuasion or incremental reorientation. But better yet would be the positive and deliberate participation in the life of the nation by all of its children, irrespective of religion or origin. At present, though, for reasons that most commentators prefer to ignore, a large part of the northern Protestant population chooses to ignore, denigrate or actively oppose participation in the life of the island as a whole – even where logic and rationality would argue for closer cooperation and participation.

In these circumstances, although many people will continue to work towards the creation of a new agreed Ireland in which all of us feel comfortable, the absence of the unionist voice in the conversation makes it difficult. The demographic argument is a valid card to play, if for no other reason than to alert unionists to the dangers of their continuing boycott of the subject. It would be better for them, and for the country, for them to abandon the irrational aspects of their position and to join the debate. If, as some argue, there are sound economic or social arguments in favour of the UK, then how could it hurt if these were explained? An open conversation between the peoples of the island implies no pre-determined outcome, and so nobody should fear it. Unfortunately, though, O'Leary's recent comments make it less rather than more likely that unionists will come out of their bunker and talk.

Sunday 14 June 2009

The Allister effect in the Westminster election

So the DUP must face the prospect of defending its nine Westminster seats against a party that may take up to 40% of its core (hard-line unionist) vote. While Allister is the public face of the TUV and may have benefited from name recognition, the candidate in Dromore was fairly unknown, indicating that the TUV may not be dependent on Allister’s name on the ballot paper.

If the DUP suffers results similar to those of its two contests with the TUV to date, the outcome may be disastrous for the party. Knowing this, voters who normally vote for smaller parties (such as Alliance) may vote tactically for a UUP candidate, thereby compounding the DUP’s problems.

Looking at the current strengths in the 18 Westminster constituencies, some possible outcomes could include:

Belfast East: Peter Robinson got 49.1% of the vote in 2005, with second-place Reg Empey on 30.1%. If a TUV candidate takes 40% of the DUP’s vote, Robinson may get only 29.5%, and if some of the 12.2% who voted Alliance ‘lend’ their vote to the UUP then Empey could easily take the seat. If anger over the allowances and salaries paid to the Robinsons continues until the election, such tactical voting may be even more likely. Scalping Robinson, the leader of the DUP, would be a coup both for the TUV and the Alliance Party. As an added bonus for the UUP it would finally give them the MP they need in order to take a place around David Cameron’s cabinet table.

Belfast North: A 40% cut in Nigel Dodds vote would bring it to 27.4% – below Gerry Kelly’s 28.6%. The Dodds brand name is now severely compromised, and while the TUV would dearly like to drive its knife deeper into the DUP’s dynastic structure, the fact that the beneficiary would be Sinn Féin may stop many DUP voters from deserting the party. If Alban Maginness stands again for the SDLP he may staunch the loss of SDLP votes to Sinn Féin – his standing has been raised by his European candidacy. So this one would be hard to call, and the TUV may not even stand if the possible outcome is a Sinn Féin victory.

Belfast South: The DUP polled barely more than the UUP last time, and less than the SDLP. A loss of votes to the TUV would ensure that this seat remains in SDLP hands.

Belfast West: It is unlikely that the TUV would bother to stand here.

East Antrim: If the TUV took 40% of the combined hard-line unionist vote, then the DUP could expect a vote of barely 30%. Although this is still higher than the UUP’s 2005 vote (26.6%), it brings the DUP perilously close to disaster. Again, strategic voting by Alliance voters could give this seat to the UUP. If Sammy Wilson does not stand again for Westminster (DUP 'double-jobbers' to step down) then a new and less well known candidate may have great trouble holding the seat.

East Derry: Gregory Campbell, if he still stands, would be in a stronger position, as he was well ahead of the UUP (the second-placed party) in 2005, with an Alliance Party vote too small to act as king-makers.

Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Any TUV involvement in this election would copper-fasten Sinn Féin’s hold on the seat. Since the UCUNF has announced that it will stand in every seat, there is now little chance of an agreed unionist candidate, so this nationalist seat will retain a nationalist MP.

Foyle: Unionism is a minority creed here, so whatever the TUV does it will not affect the outcome.

Lagan Valley: In theory Jeffrey Donaldson is so far ahead of his nearest rival (with 54.7% of the vote against the UUP’s 21.5%) that he is fairly safe.

Mid Ulster: a safe Sinn Féin seat, so a TUV intervention would just splinter the minority unionist vote further. The only reason the TUV might stand here is to humiliate another of the DUP dynasties, the McCreas, in their own back garden.

Newry and Armagh: A safe Sinn Féin seat – the TUV could take 40% of the DUP’s vote without it making any difference. It would put down a marker, though, for the impact it would have on the Assembly and local elections to come in 2011.

North Antrim: The mother of all elections, this would be a real grudge-match in the DUP’s heartland. Here Allister himself will stand, and media attention will be intense. No other party could win so it will be a personal contest between Allister and whoever stands for the DUP. If it is still Paisley senior the DUP will be effectively admitting that Allister would win against any other candidate – a psychological victory for the TUV even before any vote is cast. The outcome of a Paisley senior vs. Allister contest would probably be a pyrrhic victory for Paisley, but against another DUP candidate (Paisley junior?) Allister could win, thereby mortally wounding the DUP.

North Down: A lot depends on whether or not Sylvia Hermon stands again, and for whom. The unionist vote could be split four ways (Hermon, UUP, DUP, TUV) leaving the seat wide open. But if the TUV takes 40% of the DUP’s tally, they would have no chance of topping the poll.

South Antrim: This would be a certain loss to the DUP if the TUV stand. In 2005 the DUP got 38.2% to the UUP’s 29.1%. So a drop of even 25% in the DUP’s vote would give the seat to the UUP, even without tactical voting by Alliance supporters. Again, the scalp of another of the DUP’s dynastic leaders, William McCrea, would please both the TUV and many moderates and nationalists (McCrea is notorious for associating with loyalist murderer Billy Wright).

South Down: Similarly to neighbouring Newry and Armagh, this is a safe nationalist seat (though SDLP in this case). A TUV intervention would simply serve to forewarn the DUP of the losses it could expect in the near future.

Strangford: Although the safest DUP seat, with a 56.5% share of the vote in 2005, the sitting MP is Iris Robinson, disliked by moderates for her anti-gay comments, and by the TUV because, yet again, she is a member of one of the DUP’s ruling dynasties. Nonetheless, she is likely to win.

Upper Bann: The sitting DUP MP, David Simpson, is very vulnerable to a TUV threat. A 40% cut in his vote would bring him well below the UUP, and not far above Sinn Féin. Simpson may choose to stay in the Assembly rather than risk humiliation.

West Tyrone: A safe Sinn Féin seat, with little personal interest for the TUV. They may not bother to stand here.

So, if the TUV is not just a flash in the pan, the Westminster election coming in the next 12 months should see the DUP almost certainly losing three seats, and being vulnerable in three more. If the TUV threat lives up to expectations the DUP may lose the seats of its founder, its leader, and the heads of two of its other dynasties, retaining only three seats; Gregory Campbell (East Derry), Jeffrey Donaldson (Lagan Valley), and Iris Robinson (Strangford). That, truly, would be a disaster for the DUP. Many people, and not just hard-line unionists, are hoping that the TUV will live up to its expectations.

The DUP has only a short time to counter the TUV threat – a threat almost to the continued existence of the DUP, and certainly to its dominant position within unionism. We can expect some dramatic moves from the DUP in the months ahead, but whether they help the party or further weaken it, cannot yet be predicted.

Friday 12 June 2009

Who votes for Alliance, and why?

The graph shows a regular dip in the Alliance vote every five years – these are the European Parliament elections. Obviously many Alliance voters, knowing that their vote is going to be transferred anyway, either do not vote at all, or skip the pointless Alliance vote and go directly to their second preference.

Nonetheless, in the recent European Parliament election it received 26,699 votes (5.5%) – despite having no realistic chance of winning a seat. This number must represent a hard core of Alliance supporters who are determined to fly the flag of their party regardless. This level of 'hard core' voters is seen more clearly in the second graph, which looks at Alliance Party votes and percentages in elections apart from European Elections:

Here it can be seen that the decline seems to have reached a floor of around 4-5% of the total, and an absolute vote of around 30,000. The outcome of the 2009 European election for Alliance was entirely consistent with this.

But who were the 26,699 people who voted for the lliance party last week, and why did they give their first preference vote to a candidate who was never going to be elected?

Different elections allow us a different glimpse of the Alliance voter. Westminster elections show us that they are largely concentrated in outer Belfast; South and East Antrim, Lagan Valley, and East Belfast. Few Alliance voters are west of the Bann. This was not always the case – in earlier days the Alliance Party had received small though respectable scores in places like Mid Ulster, Derry and South Down. By 2005, however, the party was no longer even standing in Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Foyle, Mid Ulster, Newry and Armagh and West Tyrone. As the west 'greened', it seems that the 'yellow' withdrew.

The Single Transferrable Vote allows us to see which parties are the second choices of the hard core Alliance voters. The recent European Parliament election was revealing in this respect. The Alliance and Green candidates were eliminated together (causing, unfortunately, a difficulty separating their transfers, but given the two parties similarities it is likely that their transfer patterns were not hugely different).

Of the 42,463 votes cast for the Alliance and Green candidates, some 7,548 did not transfer – these were the hardest of the hard core. But 34,915 transferred as follows:

Jim Allister (TUV) – 4,284 votes (12% of the transfers)

Diane Dodds (DUP) – 2,914 (8% of the transfers)

Alban Maginness (SDLP) – 16,325 (47% of the transfers)

Jim Nicholson (UUP) – 11,392 (33% of the transfers)

Thus over 20% of Alliance and Green transfers went, as a second preference, to hardline unionist candidates. Less than half went to the only other pro-EU candidate in the election (Maginness). In terms of tribal blocks, 53% of the votes that transferred went to unionists and 47% went to the sole nationalist, Maginness (de Brún having already been elected).

This presents a strange picture of the Alliance vote. Nominally moderate, nominally pro-EU, nominally non-sectarian – nonetheless over one in 5 of the Alliance and Green transfers went to overtly tribal, strongly anti-EU candidates.

So while much of the Alliance Party's early vote (from the 1970s) has drifted away from the party either towards electoral apathy or the other, tribal, parties, one would expect the hard core that remains to be made up of committed centrists, pro-Europeans and anti-sectarians. Yet over 20% of them transfer their vote to precisely the types of candidates that should be anathema to them – and they transfer thus in preference to the more moderate SDLP or UUP candidates. Perhaps some Alliance voters are not as far removed from the tribal hatreds as they pretend?